The source and quality of a food’s protein sources are important features to consider when selecting a dog food. Dog folks who care about these things often agonize over how to differentiate among foods in terms of both protein level and quality. These concerns are justified because the protein ingredients found in pet foods vary dramatically.

However, while we all like to talk about protein quality, what exactly do we mean by that term?

What IS protein quality, anyway? A few basics:

- High quality proteins supply essential amino acids: The protein in a dog’s diet provides the essential amino acids (EAA), plus a source of nitrogen. Essential amino acids must come from a dietary source and are used for growth, tissue repair, muscle development, support of the immune system and a wide range of metabolic functions. A protein that is classified as high-quality supplies all of the EAA in proportions that are close to the dog’s requirements. Conversely, lower quality protein sources are limiting (i.e. have low levels) in one or more of the EAAs.

- High quality proteins are digestible: In addition to supplying EAAs, high quality proteins will also be highly digestible. Conversely, low-quality pet food proteins are those that are either low in digestibility, limiting in one or more of the essential amino acids, or both.

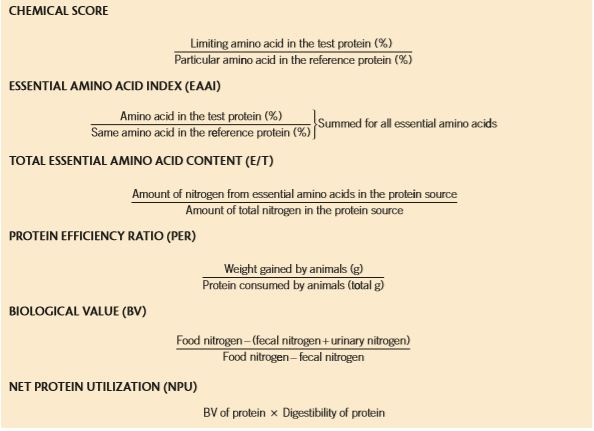

- Measures of protein quality: Nutritionists use several methods to evaluate a protein source’s quality. Some of these, such as chemical score, EAAI and E/T (see below), are conducted in the laboratory and do not involve feeding the protein source. Others, such as PER, BV and NPU, involve feeding trials with a test species (usually growing chicks). Each of these methods, like many things in life, have specific strengths and limitations. Most nutritionists agree that using several measures provides the best overall assessment of a given protein source.

From: Case, et al. “Canine and Feline Nutrition; A Resource for Companion Animal Professionals” (2011)

How does this information help pet owners? Sadly, not much. The reason is that the protein quality information that pet owners are provided is abysmally deficient. The following two platitudes continue to be the ONLY recommendations that owners can use:

- Select a food that includes a named animal source (i.e. chicken meal rather than poultry meal) and

- Prefer the AAFCO-defined distinction of meals over by-product meals (chicken meal rather than chicken by-product meal).

Unfortunately, these selection criteria do not reliably reflect quality differences among foods. It is a sad state of affairs indeed for pet owners.

The Good News: There is a bit of good news, however. In recent years, a select group of university researchers have been publishing studies that examine pet food protein quality, labeling accuracy, and methodology. A group of investigators led by Dr. Greg Aldrich at Kansas State University added to this growing body of work with a study that compared a range of protein ingredients that are used in dog foods.

Why Peas and Potatoes? They included pea protein isolate and potato protein isolate in the study group. These plant ingredients are of interest due to previous reports of a possible association between these ingredients (among others) and the development of dilated cardiomyopathy (a heart disease) in dogs (see “The Heart of the Matter“). Pea and potato protein are relatively new to the pet food scene and have not been studied thoroughly in terms of protein quality or digestibility.

The Study: The researchers evaluated 16 different protein sources. These included various forms of egg protein (the standard by which to compare other proteins), several forms of chicken, a bunch of commonly used plant proteins such as soy and corn gluten meal, and the two newbies, pea protein and potato protein. There is a lot of information packed into this study, so I will attempt to distill this into the facts that are most important for dog folks to know.

Protein Sources: The list below describes the protein sources that are probably of greatest interest (see the entire paper for an inclusive list):

- Spray-dried whole egg (In certain tests, whole egg is the standard, high-quality protein source to which other sources are compared).

- Air-dried chicken (Chicken meat dried and cooked in a hot air-drying chamber).

- Low-temperature, spray-dried chicken (By-product of chicken fat and broth industry; remaining chicken meat is cooked and dried at low temperature and pressure).

- Chicken meal (Common pet food ingredient; by-product of chicken meat industry; remaining chicken carcasses are rendered [cooked at very high temperatures, dried, and ground into a powder]).

- Chicken by-product meal (Same as chicken meal, but also contains varying quantities of chicken heads, feet and viscera).

- Pea protein isolate (New to the pet food scene; cooked and dried protein-containing fraction of yellow peas)

- Potato protein isolate (Ditto on newness; cooked and dried protein-containing fraction of potatoes).

With the exception of chemical score, the researchers utilized all of the measures of protein quality in the chart above to evaluate each of these sources. They also measured the proximate analysis of the ingredients – protein, fat, mineral (ash), moisture and fiber content.

RESULTS: This paper reported a lot of new information – multiple measures of 16 different protein ingredients. Here are their key findings:

- Chicken sources: There were several important differences in protein quality between air-dried/spray-dried chicken ingredients and the chicken meal and by-product meal ingredients:

- Because the original starting materials differed (meat vs. spent carcasses), the air-dried and spray-dried chicken products were significantly lower in ash than chicken meal and chicken by-product meal. This reflected the inclusion of bone in the latter and not in the former.

- Chicken meal and by-product meal had higher levels of two types of amino acid that are associated with connective tissue and structural proteins. This means that these sources were higher in protein types that are less digestible and less available (i.e. lower quality) than those found in the spray- and air-dried chicken ingredients.

- Available Lysine (an EAA) was lower in chicken meal and chicken by-product meal than in all of the other proteins tested. Low available lysine is an indicator of protein damage typically caused by the high heat processing used with rendered meals, which leads to the development of Maillard products.

- Chicken meal and chicken by-product meal performed significantly lower in growth assays when compared to other forms of chicken.

- Bottom Line? Chicken meal and chicken by-product meal, the two most common chicken ingredients that are used today in extruded pet foods, performed poorly in measures of essential amino acid availability and growth. By contrast, less heavily processed chicken ingredients scored significantly higher in these measures of protein quality.

- Potatoes and Peas: These ingredients are of interest because of the increase in their use in commercial dog foods and because of a possible connection with the reported increase in cases of DCM in dogs:

- Methionine: Methionine (which is a precursor of taurine) was the limiting EAA in potatoes and peas. This was not unexpected, as many plant-based protein sources are low in methionine.

- EAA measures: Overall, (again as expected), potato and pea proteins are poorer sources of EAA than are egg and some chicken sources. However, in this study, EAA measures for both pea and potato protein were higher than those for the rendered chicken and chicken by-product meals. (Wow).

- Growth assays: Conversely, potato and pea proteins did not support growth and development well. This was partly because of lower intakes and possibly due to reduced overall EAA availability in plant-based protein sources.

Take Away for Dog Folks: This study provides needed information about two commonly used dog food ingredients – rendered chicken and chicken by-product meals, and also about two newcomers to the pet food scene – pea protein and potato protein.

The bad news is that, not altogether unexpectedly, rendered chicken meals, regardless of whether they carried the dreaded by-product descriptor, performed quite poorly. Rendered meals, of the chicken variety, are one of the most commonly used protein sources in commercial dog foods. The products that were examined in this study performed worse than egg protein (expected) and worse in terms of EAA measures than several plant-based proteins. Chicken meal and chicken by-product meal were also found to contain comparatively high levels of connective tissue and structural proteins, and to have low available lysine, an indicator of protein damage that occurs during processing.

Conversely, other forms of chicken – in particular spray/air-dried forms that were cooked at lower temperatures, were found to be much higher quality protein sources. Although not commonly seen in dog foods, these are forms of chicken ingredients that should be on your watch list, as pet food producers continue to search for better quality animal-source proteins to include in their products.

Finally, the peas and potatoes thing. While this study does not provide a complete answer to the DCM connection, it does provide new information about these two protein-supplying ingredients. Pea and potato protein are both limiting in the essential amino acid methionine, which is the precursor of taurine production. Therefore, it is possible that the inclusion of these protein sources in foods, without concomitantly including additional methionine or taurine, may contribute to reduced taurine status in an animal. Like many plant proteins, pea and potato protein require balancing with other protein sources or amino acid supplementation to counteract these EAA deficiencies.

Of course, this information is only helpful to pet owners if they have access to it. Pet food companies continue to have no obligation to report quality information about their foods to consumers. In fact, AAFCO regulations actively prohibit the inclusion of quality descriptors on the pet food label. Still, many reputable companies do test their foods regularly and will provide measures of food and protein quality to pet owners when it is requested. If you worry about the ingredients in the food that you are feeding, whatever type of food it happens to be, email the company that makes the food and ask.

Be the squeaky wheel.

Demand transparency and more information about the ingredients that are in the foods that we feed to our dogs. If dog owners are expected to accept the claim of “Complete and Balanced”, we should be provided with proof of this claim, including information about the quality of ingredients. It should not be necessary to seek out and read academic journal papers to obtain this information.

Nuff said. Off box.

Cited Study: Donadelli RA, Aldrich CG, Jones CK, Beyer RS. The amino acid composition and protein quality of various egg, poultry meal by-products, and vegetable proteins used in the production of dog and cat diets. Poultry Science 2018; October; pp. 1- 8, https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey462

Thanks for the update, Linda!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome, Anita!

LikeLike

Fantastic article! Shared!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mollie!

LikeLike

I always understood that neoither pulses not cereals provoded complete proteins. There fore they should alsys be easten together.

LikeLike

Superb article! Very scientific and clear. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mind is blown by the pea and potato protein EAA being higher than rendered chicken and chicken by-product meals 😮

LikeLike

Pingback: Tastes Like Chicken – The Science Dog

Another piece of the puzzle is that grains are high in methionine, so grains + peas (or other legumes) offer more balanced amino acid profiles. No wonder the grain-free foods with lots of legume protein were problematic.

LikeLike

IS you dog allergic to/intolerant of these products? It is not the fresh produce that it advised against but the rendered and the isolates that are advised to be NOT fed.

On the other hand why feed any animal (including humans) on tapioca? It is almost pure starch.

LikeLike

With regards to sourcing responsibly, what are your thoughts on certifications such as Certified Humane (Open Farm is one of the few dog food brands that has attained this certification) and HSUS’s new efforts to establish a score card for humane sourcing of farm animals. I’m making the assumption that humanely sourced is equivalent to high quality sourcing – is that a safe assumption to make?

LikeLike

Very information post, Linda! Thank you. I’m just nearing the end of Dog Food Logic and I’m absolutely loving it. Although I now feel like I know what to look for (and to look out for) I’m now struggling to find anything that seems appropriate. Based on your post here, I can’t but wonder why is it then that veterinary specific diets supplied by purina etc. seem to be some of the worst offenders when it comes to ingredients? They tend to have by-product meals, corn gluten meal, unhealthy oils etc. – you expect the vet brand food is going to be above standards, but they appear to almost be worse…. any information I should be aware of when it comes to vet Rx diets? My girl has just needed to switch to a hydrolyzed soy food since recently being diagnosed with IBD and is going through treatment as well with prednisone – I’m hoping I do not have to keep her on this stuff!

LikeLike

Pingback: It’s Not Rocket Science….But, it IS Science – The Science Dog

Pingback: La saga du sans grains (et la maladie cardiaque) – Au Nom du Chien

Pingback: How the Sausage is Made – The Science Dog

Pingback: More Human-Grade Research… and a Rant – The Science Dog

Pingback: It’s Here, It’s Here! | The Science Dog

Pingback: Raw Evidence | The Science Dog