Most people are familiar with the concept of a “placebo effect”, the perception of improved health while unknowingly receiving a sham (placebo) treatment that in reality should have no benefit at all. Growing up, my mother referred to this as “giving someone a sugar pill”. The assumption is that because we believe that we are receiving an actual treatment, our mind tells us that we should feel a bit better. Then amazingly, we do feel better. We notice a reduction in symptoms and ultimately conclude that the “medicine” must be working. The irony is that placebos actually can be powerful medicine (or something), at least for some people, for some diseases, some of the time.

Placebos and Us: The effects of placebos in human medicine are well-documented and are described with human diseases of almost every type. The highest level of placebo effect is seen with diseases that have subjective symptoms that are patient-reported and difficult to measure directly, that tend to fluctuate in severity, and that occur over long periods of time (i.e. are chronic). Examples include depression, anxiety-related disorders, gastric ulcer, asthma, and chronic pain. In medical research, an average placebo response rate of 35 percent is reported, with rates as high as 90 percent for some health conditions. By any standard, that is a whole lot of sugar pill response going on.

Placebo Control Groups: Although the reasons that we respond to placebos are not completely understood, medical researchers universally accept the importance of considering them when studying new treatments. Studies of new drugs or medical interventions include placebos as control groups to allow unbiased comparisons with the treatment or intervention that is being evaluated. Any effect that the placebo group shows is subtracted from the effect measured in subjects who are receiving the actual medication. The difference between the two is considered to be the degree of response attributable to the treatment. If a placebo control group was not included, it would be impossible to differentiate between a perceived response (placebo) and a real response to the treatment. Today, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials are considered to be the Gold Standard of study designs by medical researchers. The “double-blind” part refers to the fact that in addition to having both a placebo group and a treatment group, neither the researchers nor the subjects know which subjects are getting the treatment and which are getting the placebo. (For more information about double-blind research trials with dogs, see “Thyroid on Trial“).

What about Dogs? Can a placebo effect occur with dogs? Possibly, but things work a bit differently where our dogs are concerned. Most obviously, while highly communicative in many ways, dogs cannot specifically tell us what part of their body is in pain, how intense that pain is, if it is abating, or by how much. Rather, we use our knowledge of a dog’s behavior and body language to determine how he is feeling. As their caregivers, we are the recorders and the reporters of our dogs’ health, symptoms, and response to treatments. Similar to human studies, this is most relevant when the symptoms are things that are not easily measured using medical tests and that are more subjective in nature.

A second important difference is that dogs are basically always blinded to treatments. Although they may understand that something different is being done to them (or that there is a strange pill buried in that piece of cheese), most people will agree that dogs do not have an understanding that they are being medicated for a particular health problem or are on the receiving end of a new behavior modification approach. As a result, unlike human patients, dogs lack the specific expectations and beliefs about health interventions that may be necessary for a placebo effect to occur directly. However, because it is the owner who reports many symptoms and changes in health to their veterinarian and also who conveys subjective information regarding the dog’s response to a given treatment, a different type of placebo effect may be in action with dogs. This is called a “caregiver placebo effect”. As with human maladies, the conditions for which this type of placebo effect has been described in dogs are those that involve subjective measures of health (pain, activity level, appetite) and that have a tendency to fluctuate in severity.

Let’s look at two examples – the caregiver placebo effect in dogs with osteoarthritis and in dogs with epilepsy.

Does Your Dog Hurt Less? Osteoarthritis is a painful and progressive health problem that can seriously impact a dog’s quality of life. A variety of medical and nutritional treatments are available today for afflicted dogs. These range from NSAIDS (ex. deracoxib, meloxicam), nutrient supplements (ex. glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate) to alternative medicine approaches (acupuncture, cold laser therapy). Researchers who have studied these treatments use subjective measures of lameness in which dogs’ owners and veterinarians numerically rate their dog’s degree of pain, mobility, and interest in daily activities in response to treatment. Some, but not all, studies also include objective measurements of arthritis that quantify the amount of weight-bearing in the affected legs and weight distribution in the body.

Arthritis Studies: In virtually all placebo-controlled studies of this type, a substantial proportion of owners and veterinarians have reported improvement in the placebo-treated dogs. However, when measured using weight-bearing techniques, the dogs in the placebo group showed no change in or a worsening of disease. Michael Conzemius and Richard Evans at the University of Minnesota’s College of Veterinary Medicine decided to quantify the actual magnitude of the placebo effect in this type of experimental trial (1). They analyzed the data from 58 dogs who were in the placebo control group of a large clinical trial that was testing the effectiveness of a new NSAID. All of the enrolled dogs had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis and had clinical signs of pain and changes in gait and mobility. This was a multi-centered design, which means that each dog’s own veterinarian conducted the bi-weekly evaluations of gait and lameness. Both owners and veterinarians completed questionnaires that measured whether the dog showed improvement, no change, or worsening of arthritis signs over a 6-week period. Neither the owners nor the veterinarians knew if their dog was receiving the placebo or the new drug.

Results: Half of the owners (50 percent) stated that their dog’s lameness decreased during the study, 40 percent reported no change, and 10 percent said that their dog’s pain had worsened. When these reports were compared with actual change as measured by force platform gait analysis, the caregiver placebo effect, (i.e. thinking that improvement occurred when there was either no change or an actual worsening of signs), occurred in 40 percent of owners. The veterinarians performed no better. A placebo effect occurred 40 to 45 percent of the time when veterinarians were evaluating dogs for changes in gait or pain. This means that not only were the owners strongly invested in seeing a positive outcome, so too were their veterinarians. This effect occurred despite the fact that all of the human participants were aware that their dog had a 50 percent chance of being in the placebo group or the drug group, and that there was no way to be certain which group their dog was in.

Seizure Study: This study used an approach called a “meta-analysis” which means that the researchers pooled and then reexamined data collected from several previous clinical trials (2). Veterinarians from North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine and the University of Minnesota reviewed three placebo-controlled clinical trials that examined the use of novel, adjunct treatments for canine epilepsy. During the treatment period owners were asked to record all seizure activity, including the length of the seizure, its intensity, and the dog’s behavior before and immediately following the seizure. The pooled results showed that the majority of owners of dogs in the placebo group (79 %) reported a reduction in seizure frequency in their dog over the 6-week study period. Almost a third of the owners (29 %) said that there was a decrease of more than 50 percent, the level that was classified in the study protocols as indicative of a positive response to treatment.

What’s Going On? Well, several things, it appears. The most obvious explanation of the caregiver placebo effect in dogs is owner expectations of a positive response when they assume an actual treatment is being administered to the dog. Whenever we introduce a new medication or diet or training method and anticipate seeing an improvement in our dog’s health, nutritional well-being or behavior, we naturally tilt toward seeing positive results and away from seeing no change (or worse – a negative effect). This is a form of confirmation bias – seeing what we expect to see and that confirms our preexisting beliefs. In fact, an early study of the caregiver placebo effect in dogs found that when owners were asked to guess which group their dog was in, the owners who said that they were certain that their dog was in the treatment group (but was actually in the placebo group) demonstrated the strongest placebo effect (3).

Such expectations may be an especially strong motivator when we are dealing with maladies that have affected our dog for a long time, infringes upon the dog’s ability to enjoy life, and for which we feel that we are running out of options. Osteoarthritis and seizure disorders were the health conditions studied in these papers, but I can think of several other problems with our dogs for which we may easily succumb to the power of the placebo effect. These include chronic allergies, adverse reactions to food ingredients, anxiety-related behavior problems and even cancer.

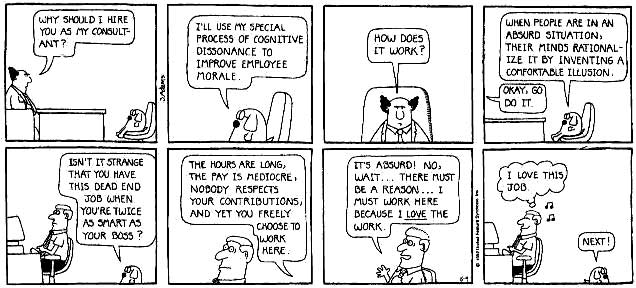

Cognitive Dissonance: Another factor that may contribute to the caregiver placebo effect is finding oneself in a state of contradiction. When we invest time and money (and hope) into a new treatment for our dogs, it follows that we will naturally have high expectations that the treatment will work. Indeed if it does not, we may experience cognitive dissonance, the uncomfortable feeling caused by holding two contradicting beliefs in one’s mind at the same time. For example, “I was told that giving my dog dehydrated gooseberry rinds would cure his chronic itching; these rinds are expensive and hard to find. He does not seem any better…… Uh oh. This is not a good feeling….”

Psychologists tell us that our brain reduces this discomfort for us (without our conscious awareness, by the way) by simply changing our perceptions. “Oh look! I am sure that the dehydrated gooseberry rinds ARE finally working. It just too some time – several months in fact. Still the effect MUST be the gooseberry rinds. YAY!” In this case, convincing oneself that the dog does seem a bit less itchy, her coat is a bit healthier and overall, she does really seem to be feeling better, immediately solves this problem for the brain and for our comfort level.

The Hawthorne Effect: Finally, a related phenomenon that is common enough to have earned its own name is the Hawthorne Effect, also called observation bias. This is the tendency to change one’s behavior (or in our case how one reports their dog’s behavior) simply as a result of being observed. The Hawthorne Effect suggests that people whose dogs are enrolled in an experimental trial may behave differently with the dog because they know they are enrolled in a trial that is measuring many aspects of the dog’s life. In the case of the arthritis studies, owners may have altered how regularly they exercised their dogs, avoided behaviors that worsened the dog’s arthritic pain, or began to pay more attention to the dog’s diet and weight.

The point is that when people are enrolled in a research trial or are starting a new medical treatment, diet, or training program and are being monitored, they will be inclined to change other aspects of how they live with and care for the dog as well. These changes could be as important (or more important) than the actual treatment (or placebo). This is not necessarily a bad thing, mind you, and is another reason why we always need control groups, but the occurrence of the Hawthorne Effect emphasizes the importance of recognizing that the thing that we think is working for our dog may not actually be the thing that is doing the trick.

Take Away for Dog Folks: When trying something new with our dogs, might we, at least some of the time, in some situations, be inclined to see improvement when it does not truly exist? When interpreting our dog’s response to a novel therapy or supplement or training technique are we susceptible to falling for the sugar pill? It seems probable, given the science. It is reasonable to at least consider the possibility that a placebo effect may be influencing our perceptions of our dog’s response to a new food, a new supplement, a new training technique or a novel treatment. This is especially true if the approach that we are trying has not been thoroughly vetted by research through double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. While the development of new medications and foods and training methods is exciting and important, we must avoid the tendency to see improvement from something that is novel simply because we expect and desire it to be so.

CITED STUDIES:

- Conzemium MG, Evans RB. Caregiver placebo effect of dogs with lameness from osteoarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2012; 241:1314-1319.

- Munana KR, Zhang D, Patterson EE. Placebo effect in canine epilepsy trials. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2010; 24:166-170.

- Jaeger GT, Larsen S, Moe L. Stratification, blinding and placebo effect in a randomized, double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of gold bead implantation in dogs with hip dysplasia. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 2005; 46:57-68.

New Science Dog Book!

“Feeding Smart with The Science Dog” by Linda P Case

Description: In The Science Dog’s latest myth-busting book, Linda Case takes on canine nutrition and feeding practices. It seems that almost everyone has an opinion about how our dogs should be fed and what diet is healthiest for them. In this timely book, Linda Case takes a look at the evidence and what answers science can provide regarding how to best feed our dogs. The book’s five sections each tackle a set of commonly posed questions, using the research of leading nutritionists to provide practical answers. If you wonder whether dogs are true carnivores, whether or not they can digest grains, why some dogs gain weight so easily, and if it is safe to feed your dog a raw diet, this book has the answers for you. Other chapters separate nutrition fact from fiction regarding omega-3 fatty acids, dietary supplements, the quality of pet food ingredients, and nutrient needs and dietary preferences of dogs. Whether you are a canine health professional, trainer, work with a shelter or rescue group, own a dog-related business or simply wish to understand nutrition and feeding better, the information provided in “Feeding Smart” will be of interest and value to you.

Hi Linda I just wanted to say how much I love your books …and how your “up on your soap box” content and illustrations/accompanying photographs really make me smile and titter at times. Thankyou 😉 Best wishes Lisa

WordPress.com | The Science Dog posted: “Most people are familiar with the concept of a “placebo effect”, the perception of improved health while unknowingly receiving a sham (placebo) treatment that in reality should have no benefit at all. Growing up, my mother referred to this as “giving some” | |

LikeLike

I would love to see a caregiver placebo study on so-called pheromone behaviour modifications.

LikeLike

I thought I’d check before buying a collar for my puppy. Very difficult though when even 2 puppies from the same litter can turn out to be totally different.

Worth a read though.

http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.233.12.1874

LikeLike

Thank you for the reference – it has two features in common with a lot of the other studies that show a positive effect of alleged pheromones; doubtful statistics (huge levels of pseudoreplication as they accumulate data from week to week, and no corrections for multiple comparisons – if you compare enough things some of them will come out different just by chance) and being sponsored by a maunufacturer of “pheromone” products. For more discussion and a trail of references to follow up you could look at https://www.researchgate.net/post/Does_anyone_have_research_or_clinical_experience_using_pheromonatherapy_in_minimizing_stress_in_dogs_and_cats.

Did you buy a collar for your pup – and do you feel that it helped ?

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I’m a horse professional and currently have two clients who have put their horses on a dietary supplement for specific issues. There’s lots of great science about why fat added to a horse’s diet is essential. The clients are seeing improvement, but it’s impossible for us to objectively measure what is going on. Since one issue is that a horse bites when stressed (and probably in pain from ulcers), it might be that the way the owner now handles the horse makes him less stressed. It’s complicated! Of course, if it’s “only” the placebo effect I’m still happy – the behavior of all involved has improved!

I’ve also seen a study about the placebo effect in animals that shows that if the drug does work, then you follow that with a placebo, administered the same way, that the placebo works, at least for a few doses.

LikeLike

This is very interesting and a lot of food for thought. I take my 14 1/2 old golden retriever for acupuncture, laser, and chiropractic. And have also started her on supplements for canine cognitive dysfunction. I think her symptoms have improved. She walks a little further, is more eager to go out and play, and has a better appetite. I don’t know if these are real improvements and if they are, whether they are due to these interventions. But at least it gives me the sense of doing something for her. I know there is no treatment for old age. I want to make her as comfortable as possible, and her final years as rich as they can be.

LikeLike

Pingback: Coconut Oil For Horses – The Cooperative Horse

Pingback: Mutt Muffs: from classical conditioning to first test with trigger – blackandwhitedog.ca